Inborn Errors of Immunity (Primary Immunodeficiencies) Clinical Care Standard

This document has been developed by ASCIA, the peak professional body of clinical immunology/allergy specialists in Australia and New Zealand. ASCIA information is based on published literature and expert review, is not influenced by commercial organisations and is not intended to replace medical advice.

For patient or carer support contact AusPIPS, IDFA, or IDFNZ.

This Clinical Care Standard aims to improve the diagnosis and management of children and adults in Australia and New Zealand with inborn errors of immunity (IEI), include primary immune deficiencies (PID), except for Hereditary Angioedema (HAE), as a separate Standard will be developed for HAE.

![]() ASCIA HP IEI PID CCS 2025211.81 KB

ASCIA HP IEI PID CCS 2025211.81 KB

GUIDING PRINCIPLES

Inborn errors of immunity (IEI) include primary immune deficiencies (PID) and are a group of more than 550 potentially serious chronic medical conditions. They are caused by defects in genes that control the immune system and can lead to frequent or severe infections and other chronic immunological conditions, including autoimmune problems.

This standard does not include secondary or acquired immune deficiencies.

High-Quality, Team-Based Care

People with IEI, including those in regional, rural and remote areas, should have access to healthcare services that are equitable, accessible, timely, efficient, integrated, safe, effective and culturally appropriate. Management should include the following:

- Primary clinical team comprising of a clinical immunologist, immunology nurse, general practitioner and in some cases a local or regional paediatrician or physician.

- Multidisciplinary team aligned with the patient’s evolving needs, such as other medical specialists, dietitians, pharmacists, dentists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, child life therapists, exercise physiologists/scientists, psychologists, social workers, genetics counsellors and transition services, working along with the patient’s primary clinical team.

- Medical and allied health approach aligned with the patient’s physical, emotional, mental, cultural and social needs and wellbeing.

Effective Communication

To facilitate and integrate care, the primary clinical and multidisciplinary teams that care for people with IEI should use effective communication to share information, knowledge and expertise with each other and the patient.

Self-Management

People with IEI should be supported by their medical team to learn about their condition, self-administration of therapies and effective self-care strategies, so that they are empowered to take an active role in managing their condition.

Shared Decision-Making

People with IEI should have the information, support and resources they need to make decisions together with expert advice and guidance from their medical team, through effective communication and shared decision-making processes.

QUALITY STATEMENTS

The following quality statements focus on 8 specific areas of care where improvements should lead to better health outcomes and an improved quality of life for people with IEI:

1. Time to first immunology appointment

When there is a high clinical suspicion of IEI (e.g. when a patient is assessed by a paediatrician or GP), they should be discussed with a clinical immunologist. When referral is made, an appointment with a clinical immunologist for review should occur within 4 weeks of referral:

- Early recognition of symptoms enables early diagnosis and treatment which can lead to better long-term clinical outcomes and a better quality of life.

- Starting appropriate treatment early can reduce the risk of infections and complications.

Immunology services should have a clinical and diagnostic pathway in place to urgently respond to infants identified by newborn screening, including those in regional, rural and remote areas.

Early diagnosis of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) and other severe IEI enables timely access to curative therapies which include:

- Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

- Gene therapy.

3. Diagnostic (including functional and genomic) testing

People with IEI should have equitable and timely access to appropriate, funded and accredited genomic and functional immune testing. This requires:

- Funded diagnostic genomic testing performed by accredited diagnostic laboratories. Genomic testing should only be ordered by health professionals with appropriate knowledge and expertise, supported by genomic medicine and genetic counselling expertise.

- Adequate staffing and resourcing of laboratories to ensure timely provision of functional and genomic test results.

- Funded and accessible highly complex specialised functional immune testing for patients with suspected IEI.

People with IEI should start appropriate treatment as soon as feasible after diagnosis, which should not be delayed:

- When immunoglobulin therapy is indicated, it should be started as soon as it is clinically indicated, ideally within 4 weeks. The person with IEI (and their carer/s or family members if applicable) requires information about intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) therapy and subcutaneous immunoglobulin (SCIg) therapy. This includes benefits and possible risks of treatment to facilitate informed decision-making regarding choice of therapy.

- When SCID is diagnosed by newborn screening, curative therapy should be initiated by 3.5 months of age.

- Many people with IEI require ongoing appropriate antimicrobial therapy to reduce complications from recurrent and/or severe infections. This should be adequately funded and readily accessible.

- Some people with IEI require immunomodulatory therapy to reduce complications from infections, autoimmune disease and/or other inflammatory conditions. This should be adequately funded and readily accessible.

- People with IEI should be regularly reviewed by their immunology team, ideally in-person at least once a year. In some cases they should have regular follow-up with their local or regional paediatrician or physician.

- People with IEI should have access to funded clinical monitoring and disease surveillance, including lung function testing, diagnostic imaging and pathology testing.

- People with IEI should have access to funded, additional vaccines. Vaccination status, and the need for further vaccinations based on each patient’s needs, should be regularly assessed, ideally at least once a year.

5. Access to home-based therapies and training

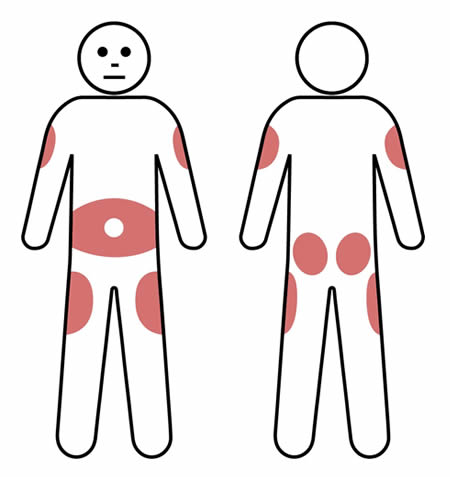

People with IEI should have access to home-based therapies, including SCIg when indicated, depending on their suitability and preference:

- Immunology clinics should have adequate specialised nurses, appropriate space and equipment to support training and regular assessment (ideally at least once a year) of people receiving SCIg.

- It is recommended that nurses follow ASCIA training competency checklists before instructing people receiving SCIg on how to self-administer, including those in regional, rural and remote areas.

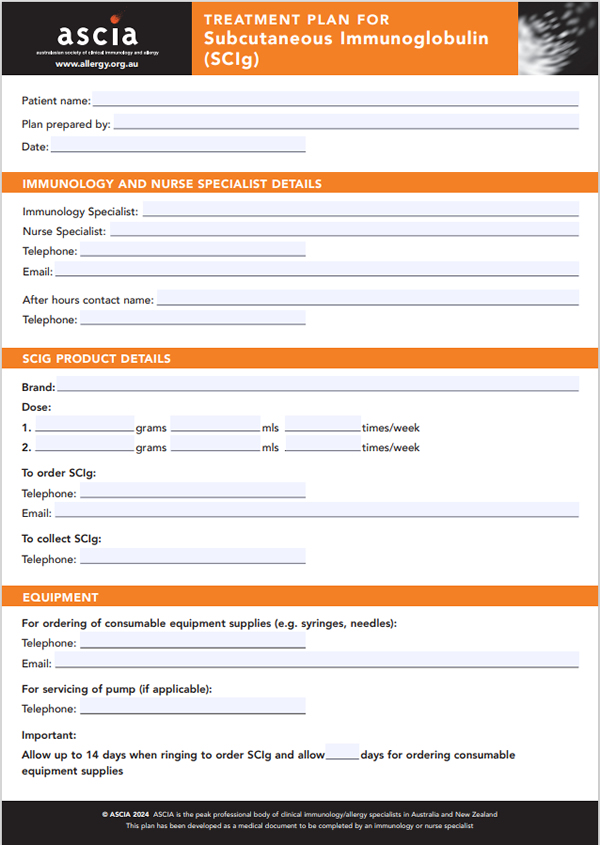

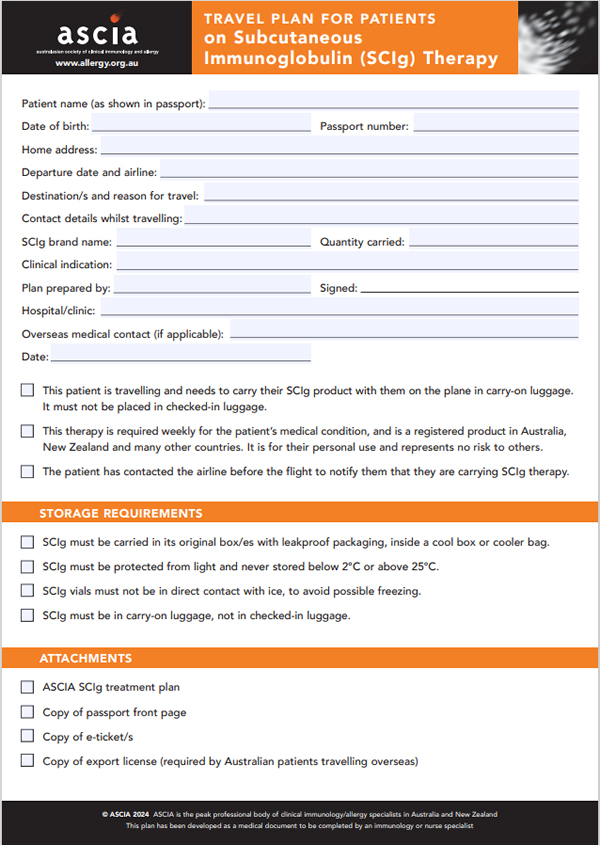

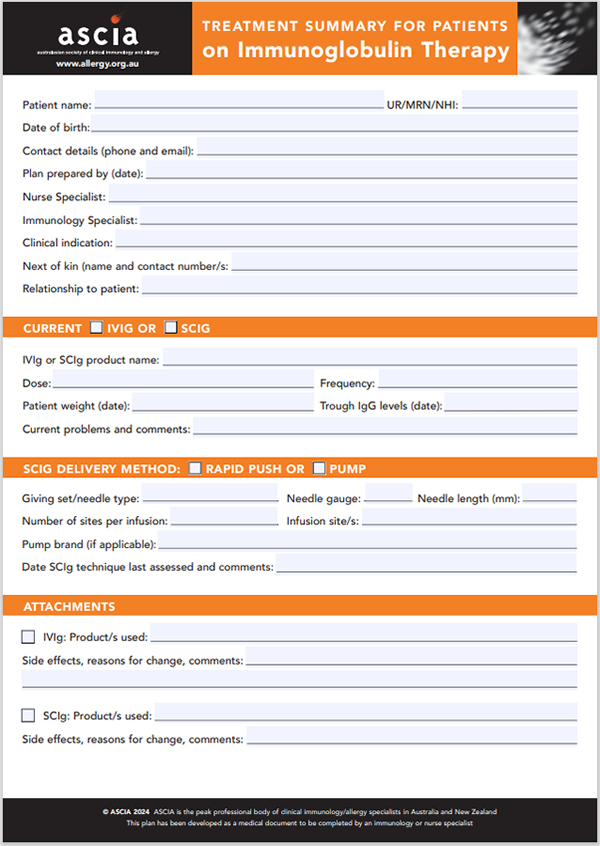

- People receiving SCIg should be provided with information and documents that support their training on SCIg, which may include a current SCIg equipment checklist, SCIg infusion checklist and SCIg treatment plan.

- Access to telehealth services is required for people receiving SCIg and other home therapies, including those in regional, rural and remote areas.

- Equitable access to SCIg should be enabled through funding (e.g. Activity based funding in Australia as detailed on the Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority website

6. Infection prevention and control

People with IEI are at increased risk of complications from infections and therefore require special consideration in healthcare settings (inpatient and outpatient), including the following infection control measures:

- Some people will need isolation from potentially infectious patients in waiting areas, emergency departments, clinics and wards.

- Adherence to local infection control procedures and additional measures to mitigate risk of any respiratory infections, not limited to influenza, COVID and tuberculosis.

Additional measures are required for infants with SCID.

7. Access to support and advice

People with IEI should be empowered by their clinical and allied health teams to make use of the information, educational resources and support services available through professional and patient/carer organisations:

- The patient’s clinical and multidisciplinary team members should empower, educate and support people with IEI (and carer/s or family members if applicable) to appropriately engage in managing their condition to optimise health outcomes.

- Clinical and multidisciplinary teams should direct people with IEI to well-established professional and patient/carer organisations in Australia and New Zealand. These organisations can provide advocacy, information, educational resources and support services to help people manage the practical, physical and psychological challenges of living with their condition.

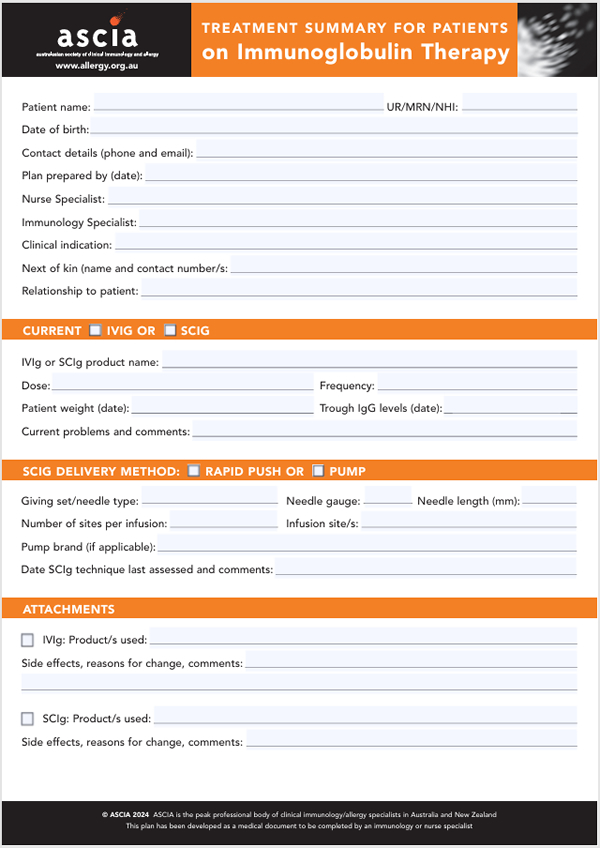

- People with IEI should be provided with a management plan such as the ASCIA SCIg treatment plan and/or ASCIA treatment summary for immunoglobulin therapy (previously known as a transfer care plan), that includes information on who to contact when unwell.

- The immunology team should be adequately resourced and available to be contacted by other clinicians in a timely manner for specialist advice.

- Healthcare providers who manage people with suspected or confirmed IEI are encouraged to discuss diagnostic and management issues with the immunology team, as well as the rest of the multidisciplinary team, where relevant.

- Physical, emotional, mental, cultural and social needs and wellbeing should be regularly assessed, and timely supportive services provided when required.

8. Transition from paediatric to adult medical services

Young people with IEI should understand their condition and learn how to look after their health independently to facilitate transition from paediatric to adult medical services:

- Young people with IEI should be supported by their clinical team and their carers to learn about their condition, self-administer therapies and self-care strategies, to be empowered and take an active role in managing their condition.

- The process should start when developmentally ready, ideally from 12 years of age.

- Genetic counselling tailored to the young person is recommended to discuss reproductive risk, even if there has been previous genetic counselling at the time of diagnosis.

- Young people should be transitioned to a corresponding adult specialist for all specialties involved in their care.

There are several publications on transitioning from paediatric to adult medical services, including the following open access published articles:

https://www.jaci-inpractice.org/article/S2213-2198(23)00464-6/fulltext

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1211524/full

RESOURCES

ASCIA website - health professionals

https://www.allergy.org.au/hp/papers/immunodeficiency

https://immunodeficiency.ascia.org.au/

ASCIA website – patients and carers

https://www.allergy.org.au/patients/immunodeficiencies

Patient and Carer support organisations

- AusPIPS – auspips.org.au

- Immune Deficiencies Foundation of Australia (IDFA) – idfa.org.au

- Immune Deficiencies Foundation of New Zealand (IDFNZ) – idfnz.org.nz

Lifeblood Australia

www.lifeblood.com.au/health-professionals/products/fractionated-plasma-products/immunoglobulins/SCIg

New Zealand Blood Service

https://www.nzblood.co.nz/healthcare-professionals/transfusion-medicine/health-professionals-medicine-datasheets/immunoglobulins/

National Blood Authority

https://www.blood.gov.au/immunoglobulin-videos-clinicians-and-patients

BloodSafe elearning Australia

https://bloodsafelearning.org.au/

International Patient Organisation for PIDs (IPOPI) educational videos

https://ipopi.org/pids/what-are-pids/

© ASCIA 2025

Content developed August 2024, updated May 2025

For more information go to www.allergy.org.au/hp/papers/immunodeficiency

To support allergy and immunology research go to www.allergyimmunology.org.au/donate

Requires frequent administration (ranging from 1-3 times per week to once a fortnight) by patients or carers at home.

Requires frequent administration (ranging from 1-3 times per week to once a fortnight) by patients or carers at home. The ASCIA Treatment Summary for patients is available at

The ASCIA Treatment Summary for patients is available at